This is some home made bread with the first cheese I ever made. This is a very simple "white" cheese (that's it's name, not just a description). It's soft, almost spreadable, and many make it with a little vinegar/lemon juice to create the curds. However, this was made using rennet, mostly as an exercise to get experience with measuring & introducing cultures, and to understand rennet-based curd development. The blue tinge is the effect of having blue items around, reflecting a blue light onto the very white cheese.

Note: This is a long article, (somewhere just under 8000 words) So go grab a tasty beverage, perhaps a little nibble (I won't judge) and find a little time to go through it. I've basically written a summary of an introductory chapter. Now when you summarize this far, there are going to be some generalized information, and of course there are going to be inaccuracies. There's plenty more detail to go into, and if you're interested afterwards, I am compiling a page dedicated to reviewing and comparing cheese making books called (unimaginatively enough) Cheese making book reviews.

Lets get on with the show...

As a "drink milk by the gallon", former farm boy, cheese is perhaps one of my favourite foods. In a cheese factory near Aberdeen, Scotland there's a quote painted on the wall that I will never forget:

"Cheese is milk's leap toward immortality"

Which is both an interesting quote, and a good indication about the original use of cheese... to preserve the nutritional benefit of milk. You might be asking, "Doesn't it preserve milk? Well, I ask you this:

"Is it really milk anymore?"

Frankly, I think the answer is no. It is chemically and biologically different, with a good portion of the original milk removed. Hence the "nutritional benefit" bit mentioned above. Which begs the question:

"What is cheese, really?"

Cheese is a fermented milk product. Meaning that we intentionally rot milk. However, before you get too disgusted, we do this in a controlled way, by introducing known-safe bacteria, moulds, and fungus into milk. In the right conditions, this combination of microbial life form an ecosystem of sorts, vastly out-numbering (and thus out-competing) microbes that are hazardous to our health. Meanwhile these microbes feast on the lactose (a form of sugar in the milk) breaking down lactose and creating lactic acid and enzymes. This acidifies the milk and create new flavoursome chemical compounds. (new proteins, and other aromatic compounds) all while trapping milk fat in networks of proteins. Which is why cheese looks, feels, tastes and smells so different from milk. Then we add salt into the mix (regulating the continued breakdown of proteins, and adding flavour). In summary, cheese is a great preservation technique because:

- You heat milk up, killing microbes that can handle cooler temperatures.

- Cultures increase the acidity of the milk (which kills a lot of unwanted microbes, and develops certain flavours).

- Cultures eat the lactose that would feed unwanted microbes, and starve/out compete them. Some also create a protective barrier (such as the white mould on Brie, created by the culture Penicillium Candidum).

- Salting/brining cheeses adds salt flavour, hardens rinds (a protective barrier), and regulates the microbial activity for long periods of time.

So in summary, cheese lasts a long time, because the existing microbes were slaughtered (pasteurization), you moved your cultures in, made them eat all the food, your new "invaders" spray acid in the face of anyone who comes near, cranked up the heat to kill anything that's left and removed most of the water (it is the basis of most life afterall), then used the bodies of the culture to promote tasty flavours, and just for fun, you then you salted the neighbourhood so it wouldn't grow anything.

Does that sound like a scorched earth policy to you? By the way, I'd be great at real estate promotion, wouldn't I? :~P

In general, cheeses that are cultured for short periods of time are ready faster, but have a more subtle flavour and softer texture. However, the longer you age a cheese, the longer the microbes have to develop flavour. This is why vintage cheddars, parmesan and other cheeses aged for a year or more have such a strong flavour. Of course, acidity levels and moisture contents are key to creating and maintaining cheese. "Fresh" (or shorter aged cheeses) like Fetta, cottage cheese, and cream cheese have a high moisture content, which reduces the shelf life to weeks, or perhaps even days after making it. However, in order to be able to age cheeses to a "fine vintage" we have to reduce the moisture content so it doesn't turn into "mystery slime" over time.

I cannot stress this enough, hygiene, temperature, and humidity control are critical to making cheeses successfully. Cheese making is a rewarding activity, but there are numerous risks if it is done poorly.

The basic cheese making process:

1. Get the best, freshest full cream (better if it's not homogenized) milk you can. Sterilize absolutely everything, utensils, moulds, cheese cloth, the bench, measuring devices, and boil them in water for at least 30 minutes. Have a pot of boiling water, as you will need to repeatedly sterilize things during the entire process. Especially when making different cheeses at the same time... you don't want blue mould overtaking your Parmesan. It might end up very tasty, but it won't be the Parmesan you intended.

2. Add Calcium to milk to restore pasteurised milks by adding Calcium Chloride using precise dose for volume of milk. Dose will be indicated in recipe.

3. Heat milk up slowly to a temperature that is ideal for your cultures (depends on the cheese being made) and maintain it. I whole-heartedly recommend using a sous vide machine and a "double boiler" arrangement.. because it makes temperature control so much easier. Please note that you won't be going to boiling temperatures so polycarbonate tubs (like those shown below) are sufficient.

This shows how I put my milk "vats" into a water baths, heated by sous vide machines. The closest one is making Halloumi, while the distant one with two vats is making Brie.

4. Add flavour cultures in precisely measured doses based on volume of milk, and allow to culture in the milk for a set period of time, indicated by your recipe.

5. Once flavour cultures have been established, add rennet (acidifying culture) or acid (vinegar/lemon juice) again in precise doses, to start the separation of curds and whey. Curds are the solid parts that will form the cheese, whey is a somewhat acidic liquid left over from the milk. Allow curds to develop over the specified time at the specified temperature for that step.

6. When sufficient separation occurs (whey runs clear) cut the curds into cubes of the specified size.

7. Allow the curds to "heal" from cutting, this might be a few minutes, or it might be considerably longer.

8. Gently "nudge" (a really gentle stir) to separate the curds. Progress to normal stirring if instructed, and ensure you're not breaking the curds into smaller pieces.

9. Once allowed to culture for the set time at the set temperature, some cheeses will need the curds to be cooked, others will skip this step and instruct you to scoop curds into cheese moulds (lined with cheese cloth or not... as instructed). Softer cheeses may just require the curds be allowed to sit together and merge, while other cheeses need the curds to be pressed together in the mould. This is to drain more whey away from the curd, and to knit the curds together.

10. You should now have an immature cheese in roughly the final shape at this stage.

11. Some cheeses will need salt rubbed into the surface, or to be submerged in a brine (salty water).. again, salt content needs to be strictly measured. Other cheeses forgo this step if they're to be consumed within days.

12. Some softer cheeses may be finished at this point, while others need to be allowed to dry at ambient temperatures for a day or so.

13. Some cheeses (in this case, Brie) is placed in a "cheese cave" (or wine fridge set to 10oC) to allow surface mould to grow.

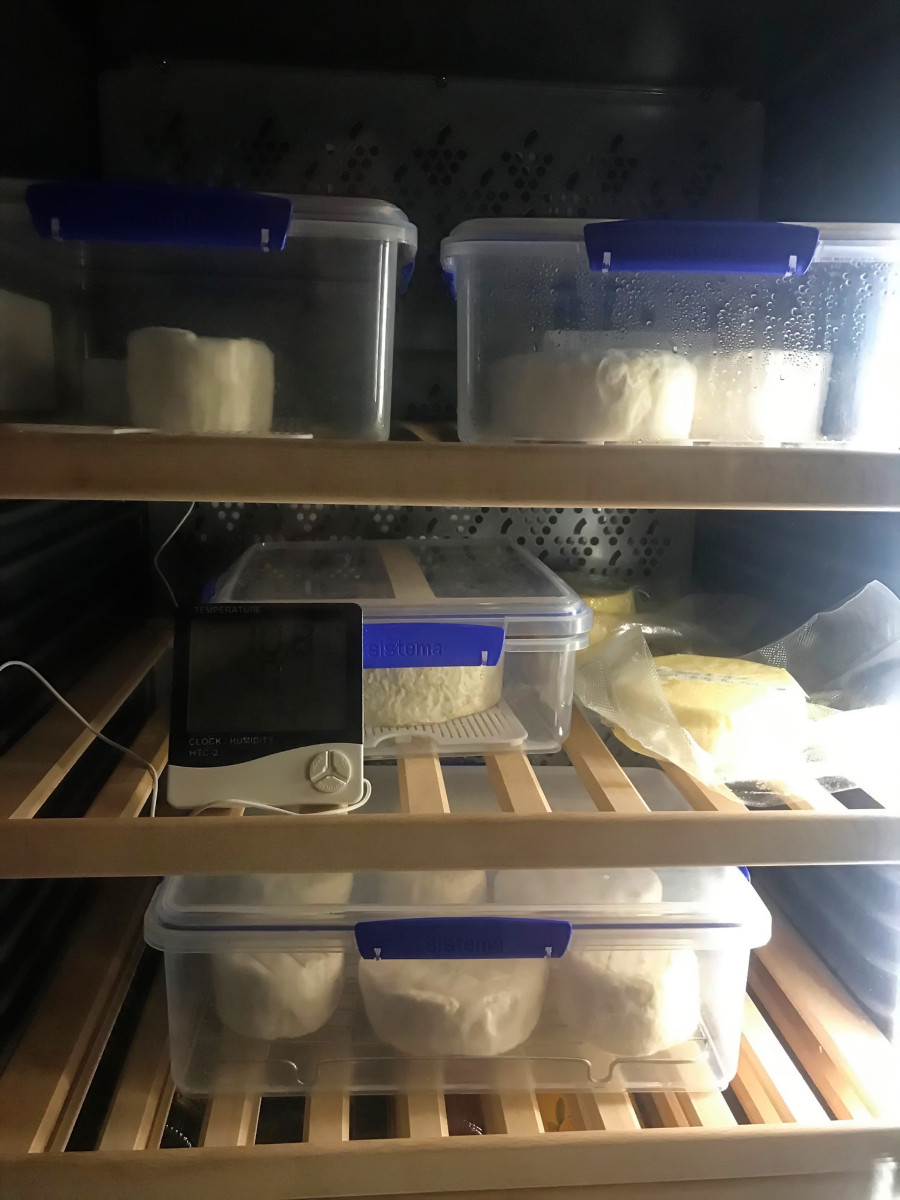

I put cheeses on draining trays inside sealed tupperware containers to maintain the high humidity needed to grow the white mould. The mould usually takes 7-12 days to completely cover the cheese. If you didn't include the mould into the original milk culture, you may have to spray it on now. Here's the mould growth at 5 days...

14. If you have a completely mould-covered cheese, (mine took 10 days) it's time to wrap it, in special micro-perforated cheese paper (available from cheese suppliers, and even found on eBay). Then stick it in your normal household fridge that runs at 4 degrees or so for final aging. Right now, the cheese will be rubbery, perhaps a little "chalky" so it's not recommended that you eat it yet. Depending on how flavoursome, and "gooey" you like your Brie, in 2 weeks, it will be soft, but not "gooey" and the flavour will be mild. In 4 weeks it will have a more developed flavour and the texture will be definitely more "gooey".

Other cheeses do not need fancy paper to wrap, some use wax, others use jars full of brine, others are sealed in vacuum bags. Did you remember that Halloumi vat in the photo above, well here is the end result:

15. Aging cheese varies from weeks, to months, or even years. If you're making long-process cheeses, it's worth dividing the batch into several small ones, so you can taste the difference of longer-term cheeses at different stages without ruining things "down the track". Some cheeses go through a bland stage that has less flavour than "fresh" cheeses, but give it enough time, they then have a creamy/buttery flavour, then vaguely nutty, then develop a real bitey flavour that might be best described as "fruity" over time. You may find that you like a "younger" stage of some cheeses, and older stages of others. This is part of the cheese making process, and will help you to pair food and drink with them accordingly.

Ultimately, cheese making has no guarantees. It's also possible to change one little thing in one stage, and substantially change the end product. There's a 2oC difference between Swiss cheese and Emmental. Despite everything else being identical. So if you get it wrong, it's probably not ruined, unless there's something growing that you know shouldn't be growing into it. Once you get enough experience, you can use sight, smell, taste, touch, and even sound (some people tap wheels of cheese and listen to the sound in order to discern how harder and longer-aged cheeses are going) Pretty quickly, you'll be able to judge what works, what doesn't, and what to do about it... as long as you keep detailed records so you know what happened and when.

Is YouTube and the Internet enough to learn about cheese?

Frankly, when you're just starting out, you might be tempted to just learn things "on the cheap". I was not willing to risk poisoning my friends and family, so after procrastinating for about three months, I opted to do a course. Now this might not be entirely necessary. Making some types of cheese is very easy, and I would strongly suggest you start there. If you like it, and want to progress further, and if you want to get the best foundation, I'd strongly recommend that you do a course.

There are plenty of courses available, especially in capital cities. However they often fill up months in advance (or get cancelled). Courses are available through a number of providers, some are run by TAFEs and similar educational institutions. Others are run by professional roaming instructors (hopping from town to town or city to city as demand dictates), some are part of homesteading and cooking workshops. So try a little search online, and find who is operating in your area, when, and how much they cost.

Now I will warn you that if you do an "Intensive" or "Weekend course".. it can really be intense. You will likely be making multiple cheeses, perhaps a yoghurt, just for fun, a Fetta, a Brie, a Blue Vein, a Halloumi, and probably some form of harder cheese like a Cheddar. You won't be making these one after the other at some sort of sedate pace. You'll be doing these concurrently, switching back and forth between one cheese and other as timers and temperatures dictate. Oh, and by the way, did I mention you'll probably be monitoring things over your breaks as well. My course started at 8am sharp and we didn't really stop until everything was cleaned up (for the 50th time that day) and stowed at 4:30pm.. or later.

Remember how that was a weekend course... well don't expect to be recouperated on Monday morning. Especially if you're not used to being on your feet for hours at a time. Now it may seem insane to teach this way, but I believe it's invaluable. It teaches you how to make cheeses concurrently, and gives you realistic expectations on what you alone can achieve in a day of cheese making. It makes you think about how involved each recipe might be.. some require 15 mins at most to make, while others require daily tasks that go on for weeks, or even months. Once it reaches a certain point though, it's basically ensuring the cheese is maturing in the right temperature and humidity.

Of course, once you've done a course, and gained some experience, there's nothing wrong with trying recipes from the Internet. I just think a course will help you to get the results you're looking for from any recipe... no matter where it may have been sourced. Not all recipes are created equal, so keep that in mind. I blamed myself for following certain recipes that skipped essential information, until you read about 35 pages down in the comments where someone says that it won't work unless you do ...<insert activity/ingredients/general arcane ritual involving sacrificing extra cream to the cheese gods>

Getting equipment and cultures:

The simple fact is that most kitchens have more than enough gear to get you started in cheese making. However, there are a few things that you will absolutely need that might not be in your kitchen:

- An accurate set of scales. I get by on my 10Kg, 2g resolution weight scales because I use volume for my cultures (see next point). However, if you measure your cultures by weight, you're going to need a very accurate set of scales indeed. (Think, 0.01 gram resolution) Scales are incredibly important for measuring salt for dry rubbing cheeses.

- For volume measurements:

- 1mL syringe. (No needle, just the syringe bit) Yes, there are times you just want a fraction of a mL commonly used to add sodium chloride, liquid rennet, etc.

- Cheese makers measuring spoons.

Very small measuring spoons - For cultures. This is how I measure things as a home cheese maker, and the slight variances in cultures mean that my cheeses have a degree of variability. You know how people have spoken of "a dash" of this, or a "smidgeon" of that, a "tad" of something else, a "pinch" here, and a "drop" there. These are actually completely "legit" measurements and they're all fractions of a teaspoon.

- Tad - 1/4 of a tsp.

- Dash - 1/8th of a tsp.

- Pinch - 1/16th of a tsp.

- Smidgeon - 1/32 of a tsp

- Drop - 1/64th of a tsp.

- For cultures. This is how I measure things as a home cheese maker, and the slight variances in cultures mean that my cheeses have a degree of variability. You know how people have spoken of "a dash" of this, or a "smidgeon" of that, a "tad" of something else, a "pinch" here, and a "drop" there. These are actually completely "legit" measurements and they're all fractions of a teaspoon.

- Some sort of double-boiler setup. I use polycarbonate tubs, but you could easily use a saucepan with a smaller one in it or a larger one on top of a small saucepan. DO NOT USE ALUMINIUM COOKWARE (the whey is acidic and will eat your pot, and ruin your cheese) You're far better off in stainless steel but note that brine solutions can rust the best stainless pots. So boil them up to make the brine solution, and get that cooled brine into a plastic container as soon as possible.

- Please note that most cheeses (to make any meaningful quantity) will start off with 4-8L of milk as a minimum. As you get to harder cheeses the yields will drop, so you might consider 8-10L as a minimum capacity.

- A whisk with a sealed handle. A lot of whisks will have hollow metal handles, they're difficult to clean out, or may have anti-bacterial residue left in them from the last washing. This kills cheese making cultures. If you start using large batches of milk in your cheese making, and use large saucepans, you'll want a really big whisk. I found mine at the local commercial kitchen supplier.

- Thermometers! You're going to need at least two. One for your water bath, the other for measuring the milk temperatures. If you're going to make more than one batch at a time, you'll need several. Many analogue thermometers are NOT accurate. I recommend electronic ones that have additional useful features such as alarms when certain high or low temperatures are reached. Some have timers, and others have clock/humidity functions. You'll need a separate type for your cheese cave.

- Highly recommended: A sous vide machine for temperature control and heating of the water bath. There are many manual ways to make cheese temperatures do what you want on a budget but once you have a set and forget temperature option, you never want to go back.

- Cheese cultures, yeah.. you're going to need some of those. When they mention that it is good for say, 100, 120, or 300L that's the milk, not the resulting cheese. I recommend that you look into the suppliers in your area, or look at the Australian ones if you're here in the land of Oz.

- Curd cutters: When you're just starting out, cutting your curds with a long sharp knife is possible, but as you progress in your cheese making, you'll need to cut the curds into finer cubes than you can do with a knife. Curd cutters are effectively a frame with vertical and/or horizontal blades/strings for cutting the curds. Mine is a frame that has bunch of holes, and you thread fishing line into them at the appropriate spacings. One end of mine has vertically aligned strings so I can do the easy vertical cuts lengthwise, then width-wise, I then run the horizontal aligned strings through in one direction only.

It's worth noting that cheese making course providers also often sell the cultures, and equipment that you most likely used in the course, or can direct you to the people who do. This benefit cannot be understated, as cultures from differing sources, may have differing strengths and need the ingredient amounts to be adjusted accordingly. Also, course attendees are sometimes offered discounts on the equipment and cultures... which can be really handy too. Having said that...

I found that shopping around for equipment in the local Nisbets (a commercial kitchen supplier) saved quite a bit of money on the polycarbonate tubs and baths, offered cheaper and better thermometers, and had a better range than my instructor's cheese-specific store offered. Not a criticism, just an unsurprising fact. I bought my cheese press from eBay at a surprisingly low price, but I bought my cultures, my cheese moulds, and most of my cheese-specific utensils from my instructors store.

Unfortunately, I ran into a problem when I started to make big honkin' wheels of cheeses with a diameter of 25cm or more, and potentially 5-15cm deep. Wrapping Brie's of this size required much larger sheets which I found prohibitively expensive or difficult to obtain. So I went to another supplier that had sheets 60cm x 60cm. I learned that what I gained in size, I lost in expense. So now I make many small-to-medium cheeses... mostly for this reason.

Warning: Do not use Aluminium utensils or cook pots to make cheese... the acidity will react with, and destroy your metal and make your cheese taste bad. To make matters worse, you often need to brine your cheeses in very salty solutions, which also doesn't help. To sum up, you absolutely need stainless steel, or plastic/glass materials to handle the acidic curds and whey, and the salty brine. However, even my more expensive Scanpan stainless pots are showing signs of rust on the bottom after boiling the brine solution.

Still with me? I haven't scared you off with tales of my rotten milk? Here's some background information that might help you to understand the process a little more... or as I like to call it:

Some interesting cheese making knowledge to impress people at dinner parties...

...or not. Apparently they're a vegan or are lactose intolerant... or think "soap operas" are the "culture" you were talking about. If 0 for 3 is your usual score in social situations... you're definitely not alone. <Cue rueful smile and "back of the head" scratching here>

A little bit of history and geography regarding cheese:

There's just such a variety of cheeses out there, and Australia, despite claiming to be "multicultural" seems to lag behind Europe's cheese range and tastes by at least... err... 20 years. What we get in stores is just the tip of the iceberg.

Over time many cheese varieties have come to be strongly associated with the cultural identities of many countries and regions. From soft and salty Fetta, to smooth and creamy Brie, addictive and salty Halloumi, onto vaguely errr... nutty? Jarlsberg, then to hard bitey vintage cheddars, and all the way out there to the pungent "Washed rind" varieties like the french Reblechon or german "Limburger" which can smell worse than smelly feet... yet taste amazing... if you're brave enough to try it. This is far from an exhaustive list, and there are far more exotic cheeses, some weird, some wonderful, and others highly dangerous to eat, illegal to sell (yes there are "black market cheeses"), and all are still culturally significant to someone.

Each of these cheeses come from a specific area, but have you ever wondered why?

In the old days, keeping cultures alive long enough to transport them was nigh on impossible. As such, different areas had differing native cheese making cultures, so the cheeses made in France, were fundamentally different from cheese made in Poland, Egypt or Italy. Camembert is originally from the village of Camembert, which is in the Normandy area in France. Similarly, Brie is also from the Brie Region, located between the Seine and the Marne valleys in France. Parmesan (Parmigiano Reggiano) also has a local region, that roughly covers the regions of Emilia Romanga, and Lombardy. But perhaps more famously, the towns of Parma, Reggio Emilia, (hence the name) with less famous towns including Bologna (probably famous for Spaghetti Bolognese), Modena, and Mantua.. which I have no idea what the last two towns might be famous for, but I'm sure they have some great food too.

Psychological & legal barrriers to cheese making. Parmesan cheese has a "Protected Designation of Origin" status, so can you make Parmesan or other protected cheeses at home?

To be officially recognized as Parmesan, there are incredibly strict limits on where the cows were raised, what breed they were, what they were fed, and how the cheese was made. Even if you have everything else right, but run a farm just outside this area, you cannot officially call your cheese "Parmesan". Can you make a viable alternative? absolutely... but lawyers might get involved if you sell it as "true traditional Italian-style Parmesan".

Wikipedia states:

All producers of Parmesan cheese belong to the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano-Reggiano (or in English, the "Parmigiano-Reggiano Cheese Consortium"), which was founded in 1928. Besides setting and enforcing the standards for the Protected Designation of Origin (or PDO), the Consorzio also sponsors marketing activities.

There are many limitations of cheese definitions, usually enforced by some governmental/cultural and/or corporate cabal. Much like Port Wine must come from Portugal, or Champagne must come from the Champagne Region. For a home cheese maker, that doesn't stop you from being able to make something similar, and perhaps to your taste.. even better. Officially recognized or not.

But let's get back to basics...

Ancient & traditional cheese making methods:

Lets be clear here. People have been making cheeses for centuries, using far more primitive equipment than we have available now.. most of it found in almost any home kitchen. The first cheeses were most likely an accident. However, over time, accidental events became intentional acts, as certain substances and techniques were discovered to make delicious cheese products (even though the exact science behind it might have been poorly understood at the time). Somewhere along the line, this created the practice of harnessing cultures (like rennet) from the gastro-intestinal tract of cows, sheep, and other herbivores, and culturing milk with it in caves, larders, and basements. Was the product from each attempt always edible? Of course, not. Was it consistent in quality and flavour? No. However, from these humble beginnings, and many failures, we now have the diversity of cheeses we enjoy today.

Modern cheese making:

These days are much easier. Starting with laboratory grown and almost 100% pure cultures, refrigeration, and speedy delivery, with the right ingredients, it's entirely possible to make cheeses of almost any type, anywhere. Of course, certain cheeses are proprietary, and much like a certain fried chicken chain, might have the equivalent of "11 secret cultures and techniques" however that doesn't mean you can't make something "in the ball park" that you might actually prefer.

While truly consistent results requires exact repetition of all the variables, home cheese makers won't be able to exactly replicate the situation from one batch to the next. However, I personally enjoy the challenge, and the subtle (and sometimes, profound) differences in my cheeses.

A little side note: Last year, I was making Parmesan (I do harp on about Parmesan, don't I!) and was making it in three different batches. While focusing on the second and third batch, the first was left to cure longer, and at a lower temperatures than the other two. In the end, I jokingly labelled it "I can't believe it's not Parmesan", and aged it for a few months. It was a far more moist cheese, softer, and while it had the Parmesan taste, it was milder, and creamier. I gave it away to family, and they made a request for more. However, I must freely admit, my notes on that batch were lost somewhere, so I can't replicate it. Morals to the story; even mistakes can make delicious cheeses, and always make, and keep notes somewhere safe.

Despite not having true industrial-grade controls, home cheese makers can certainly make cheeses of higher quality than those often bought from a supermarket. However, I must warn you that it can be a very involved process for some types of cheese, while others it's surprisingly easy. But if you think making cheese is a great way to save money... you're probably getting into it for the wrong reasons.

To be effective in "saving money" making cheese, one or more of the following conditions are likely to be needed:

- You have access to cheap, safe and fresh milk. (Don't skimp here, out of date or short-dated milk is unlikely to make a good cheese).

- You intend to make a lot of cheese.

- You have the ability to age cheeses efficiently and at low cost.

- You're either willing to put the labour in yourself, or you have volunteers.

Good reasons to get into cheese making:

- You have an interest in making cheese, yoghurts, and other cultured dairy products. Including unusual types that you can't buy in your area.

- You might want to know what goes into your foods, so making it yourself makes this determination much simpler.

- You have a surplus of milk and want to preserve it for later use.

- You like the pro-biotic effects of fermented foods.

- You don't mind the somewhat variable results of home cheese making.

- You have a big family and/or lots of friends, who you can give excess cheese to. Making cheese can be a time consuming process. Making two small cheeses might be fine for simpler cheese recipes, but when you have to make cheeses over days, then age some cheeses for months, perhaps years, you will eventually want to make larger batches to improve the ever-present "effort versus reward" ratio. However, starting with smaller batches enables beginners to learn in more frequent, smaller undertakings, it allows you to make a diverse range of cheeses with less milk, and it also allows you to manage surpluses while minimizing the cost of failed batches.

Ingredients of Cheese:

Milk:

No discussion about cheese making is complete without a discussion about the primary ingredient, milk. Milk varies a lot, but it fundamentally has something like the following composition:

- Water - 80-90%

- Lactose (a form of sugar found in cheese) - 2-6%

- Fat - 2-6%

- Proteins 3-5%

- Minerals - 0.5-2%

Now I know the higher percentages add up to more than 100%, but I'm trying to say that when one is high, another one is typically lower.

Before you get into full cream, low-fat, skim, no fat varieties be aware that there are a number of different milk producing animals out there that are used for cheese making around the world. However, whether you have a cow, sheep, goat, camel or yak, each type of animal produces milk with differing levels of fat, protein, lactose and water. Of course, there are individual differences where one cow may have a different level of fat to another, and this comes down to the genetics of that individual, it's health, diet, and even climate of the area it was raised and milked in.

Cheeses made from cow milk typically go a creamy, or yellow colour over time as they age due to the presence of carotene (the same chemical that makes carrots orange). The Spanish cheese Manchego is usually made using sheep milk, and comes across as pale creamy colour, but not usually as yellow as cows milk might make it. Cheese makers around the world opt for more unusual milks to make cheeses from, such as goat's milk, which will make a very white cheese indeed. Some people even use llama, camel, yak or even buffalo milk, depending on the availability and local culture. Regardless of the milk used, please note that small changes in milk composition can have a significant impact on the resulting cheese. Those changes might present themselves in looks, flavour, aging times, shelf life, or a combination of some or even all of the above.

It is for this reason, that Parmesan has such stringent conditions to be officially recognised as "True Parmesan". Where the cows are raised, and what they might typically feed on simply by being there makes for a specific flavour, and has as much impact as the cheese making process itself. They control this to ensure there is an identifiable Parmesan cheese, and establishes a globally-recognized brand of cheese while encouraging a high degree of quality control. It also allows dairy farmers and cheese makers in the area to sell their products, and real estate for a substantial premium.

What if I don't have access to a dairy to get my milk?

It is entirely possible to make cheese from store bought milk. However, not all store bought milk can be used. First of all, the best kind is the milk with the highest fat and protein content. Skim milk, or no-fat milk is unlikely to make a cheese well, (with exceptions) simply because the ingredients that help to make a good curd (what cheese is made from) have already been either reduced, or entirely removed. The easiest form of milk to make cheese from, that's widely available is full-cream cow milk, pasteurized (sanitized by heating and then cooling rapidly) but not homogenized (that means the cream is still thick enough to float to the top).

Skim milk is sometimes mixed with full cream milk to reduce the fat levels "a bit" relative to the protein levels (the fat/protein levels are very important in cheese making, as curds are effectively globules of fat trapped in network of proteins). Parmesan is usually made with roughly half full-cream and half "skim" milk. If you use nothing but full cream milk, you get a similar cheese called "Romano". It doesn't quite have that hardness that Parmesan is known for due to the extra "creaminess".

Raw milk, the debate rages:

Ok, so people are used to pasteurized milk because it's the industry food-safety standard in most countries. However, people lived off raw milk for centuries without problems, and it is in my opinion, a better starting point to make cheeses once you become an experienced cheese maker. I must warn you that if you use raw milk, you cannot sell the cheese in many places. It must be for personal consumption, because there are still risks. If the cow is not healthy, that can make for unhealthy milk. Raw milk also has a shorter shelf life, so it's essential you use it up quickly. Many people believe it is unsafe because it poses a risk to young children, people with a compromised immune system, and pregnant women as some pathogens can impact them more severely. However, if the raw milk is from a reputable source, transported quickly and safely... the risks are vastly reduced, and the cheese has a flavour depth and complexity that cheeses made with industrially homogenized milk can't match.

Please note: It's actually illegal to buy (or perhaps more importantly, sell) raw milk in some countries. The only way to get raw milk in these countries is to own a cow (or whatever animal) yourself, and milk it directly. However, it may not always be that dire. There are some farmers who allow you to buy a "share" in a cow. (You pay for a share of the feeding and caring costs, and you get a proportional share of the milk) and this is a way people get around this legal restriction in the U.S... and probably other countries as well. If you go that way, I would strongly suggest that you get involved with the time-shared animal, see if it's healthy, learn the differences between milk just after birth, and the seasonal variations. You'll learn so much more from that process, and ensure that you get the most from your investment. Besides, what farmer doesn't want a helping hand?

Here in Australia, it is entirely possible to buy (legally) raw milk again in the shops, and this seems to be a recent development. However, it's also frighteningly expensive (say five to seven dollars per litre). Fortunately, I know of a certain commercial, well maintained dairy in my home town, and I buy the milk raw at $0.50 per litre whenever I visit. I use that milk exclusively for cheese making, and for personal consumption.

My course instructor strongly encourages people to pasteurise raw milk at home before making cheeses of it. The instructions to do so can be found here:

https://www.cheesemaking.com.au/pasteurisation-of-milk-for-home-cheesemaking/

Non mammalian milk:

I don't know if anyone has tried to make cheese from soy milk, or nut milks of any kind, but frankly I'm of the opinion that milk comes from lactating mammals. If you buy the kind of milk made from plants (say soy milk) please note that it isn't really a milk per se. It's more a milky "juice". However, while I am a big fan of coconut milk and coconut cream.. I just wouldn't try to make a cheese out of them.

I've read that some places offer "vegan" cheese, but I have not tried them myself, nor am I convinced that it is actually a cheese for that matter. Sometimes "vegan" ingredients scare me more than the "real" stuff.

Cultures and Rennet:

Each cheese needs to be made with different cultures of moulds, bacteria, and fungus. There are two broad categories of cultures:

- Mesophilic: This roughly translates to "Medium loving". It's a group of cultures that work best in temperatures from 14oC up to 32oC or so (57-90o in Fahrenheit if you're an imperial unit user). These are usually used in making softer-to-medium hardness cheeses such as Fetta, Brie, Swiss, Edam, Gouda, cream cheese, and others.

- Thermophilic: Roughly translated to "hot loving", usually cultures best at temperatures over 32oC up to 52oC or so (the upper limits vary a bit depending on who you're talking to, I've seen numbers written as high as 60oC in scientific articles and cheese making books). These are used in your high temperature (which usually means either stretchy or hard cheeses). These are often used in Mozzarella, Romano, Swiss, Parmesan, Gruyere, Provolone, Emmentaler/Emmenthal (however you spell it, there seems to be, some variation from one source to the next).

Time and temperature has an effect on identical cultures:

Each culture grows best in ideal conditions (like all things) and as such, have most effect in milk at suitable temperatures. Each culture has unique ways of changing the milk, both desirable, and less-so. Cultures can be used to complement, or mitigate the effects of others, so recipes need to take the combined effects into consideration.

There are a number of cheeses which use mixtures of cultures from both mesophilic and thermophilic categories for flavouring, acidity control (curd development), texture control and/or rind development. You can have the exactly the same mix of cultures in the same milk, and depending on the amount of time the milk spends in lower (mesophilic) temperatures, and later, higher, (thermophilic) temperatures, you can get very different cheeses at the end.

A brief look into the microbial ecosystem development as cheese is made:

Obviously, milk has to be heated up from standard refrigerator temperatures that are aimed at slowing microbe reproduction, (to keep food fresh for longer), and for cheese making this is far from ideal. Once raised to between 15oC and 32oC, mesophilic cultures start the cheese making process, adding flavour, and "eating" the lactose and other nutrients as they go. If the temperatures stay at the mesophilic range, thermophilic cultures (if present) cannot out-compete the mesophilic cultures on their "home turf". As such, the cheese will be dominated by whatever mesophilic cultures are present, and the traits they create in the finished product, in roughly the proportions they're added.

The more time cultured milk stays at mesophilic temperatures, the more lactose (or "food") from the milk is eaten. This leaves less for the thermophilic varieties, and as such offers some level of control for mesophilic/thermophilic balance.

However, in meso/thermophilic combination cheese recipes, the temperature is raised further to allow thermophilic cultures to take over, and further develop a different range of flavours. As temperatures move above 32oC, conditions become less favourable for mesophilic cultures. Depending on how high the temperature goes beyond this point, it might merely slow mesophilic reproduction down as the temperatures get too high, or if temperatures go high enough, even cause the mesophilic cultures to die off completely. Please note that their effects aren't lost, having made their changes to the milk already.

How quickly you raise the temperature determines the time spent in each range. So this can have an impact on the finished product. Many recipes specify a rate (say 1 or 2 degrees Celsius per minute) during crucial parts of the process.

Thermophilic cultures do best between 32oC and 60oC, however some cheeses, once the culturing has been done and the flavours are nearly at the finished stage, then involve cooking the curds in temperatures as high as 92oC in the whey that was produced when making the curd. This adds another chemical refinement to the finished flavour, but most importantly, creates a rubbery, elastic style texture that defines cheeses like Mozzarella, Halloumi, and Bocconcini. The down side to this is you kill all but the hardiest of thermophilic cultures, so this cheese is largely "dead". Without a living ecosystem, these cheeses are more susceptible to microbial attack, and as such don't last long outside of vacuum sealed bags, or brined in jars.

Notes about particular unusual cultures:

Propionic Shermanii:

One bacterial culture, "Propionic Shermanii" is is an important flavouring culture in semi-hard cheeses, and is responsible for the large bubbles/eyes found in Swiss style cheese. (Also Gruyere, and Emmanthal/Emmentaler). However, there are usually other cultures working with Propionic Shermanii to make the finished flavours of each of these cheeses.

Brevibacterium Linens:

If you have come across a particularly smelly cheese (probably smells like stinky feet, with a slight sulphur undertone), and noticed an orange skin, then you have probably come across a "washed rind" cheese grown with this rather pungent culture. You might be wondering "Why on Earth would anyone consider making something that smells so bad, let alone consider eating it?". The truth is that while the skin is indeed stinky, it imparts a host of complex flavours onto the core of the cheese, that cheese connoisseurs adore, it also forms a potent barrier that preserves the cheese from wild microbe infection, and stops all but the most hardy people from nibbling your cheeses.

Making cheeses with this culture is not for the "faint of heart". It requires sparing use, absolute commitment to the process, and it is unforgiving should you miss a deadline at any stage. A good washed rind cheese can take weeks of daily washing, sometimes more than once a day. Failure to manage your cheeses results in an overpowering and relentless stench likely to induce vomiting from across a very large room. As such it's highly recommended that you grow each of your cheeses in individual tupperware containers if possible to avoid cross-contamination should one fail.

Rennet, and why it's used.

Rennet is a bacterial culture aimed at "acidifying" the milk so curds can properly develop. Rennet can come in powder, tablet or liquid form (I use the liquid) and can come from both animal-based and vegetarian sources. (I don't know the details of where the vegetarian option comes from, but I use it and it works well). Some "flavour" cultures do provide a degree of acid to the milk, and this can contribute to the curd development. However, it's often not enough to make the firm curd needed for most cheeses, so rennet is added usually 30-50 minutes AFTER the flavour cultures to ensure that the rennet doesn't overpower the flavour cultures.

Where to go from here?

Cheese making is a rather unusual activity in this mass-produced, bulk purchased, excessively-packaged world. However, many crafts are experiencing a renaissance at the moment (thank you everyone who've helped me along the way), so there's a surprising number of people trying to relearn the arts that were more common in our grandparents day. Have a look at the following cheese making sites:

- https://www.cheesemaking.com.au

- https://www.littlegreencheese.com/

- https://curd-nerd.com/

- https://www.cheeselinks.com.au/cheesemaking/

There are a number of good cheese making books, online videos, and such. I'll update my cheese making book reviews up in my cheese-making-book-reviews page when I get a chance, and include some videos when I find the ones I've watched again.

This is my very first Parmesan wheel that has been aged for 4 years or more. It weighs in at over 2.3Kg (after scraping a little mould off) and it is amazing!

Phew, that was a long one, wasn't it. No unnecessary Parmesan was harmed in the making of this article.

Have fun, and happy cheese making!

Ham.

{unitegallery cheese_making_photos}